|

Home Intro Technical History Crew Models Gallery Kriegsmarine Archives

More Forum  UPDATES UPDATES |

Introduction.

On 18 May 1941, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder set in motion the most dramatic test of the Royal Navy’s ability to defend the North Atlantic shipping lanes to date. Operation Rheinübung would see the first use of the Kriegsmarine newest warships, the battleship Bismarck (Captain Ernst Lindemann), and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen (Captain Helmuth Brinkmann). Command was vested in the Admiral Gunther Lütjens, recently returned from commanding the highly successful Atlantic sortie by the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Based on his earlier experience, as well as the separate operations of pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, great things were expected. Raeder’s timing would appear to have been impeccable, for the strength of the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Tovey, KCB DSO, RN, was at a low ebb. Though Admiral Tovey theoretically controlled the Royal Navy’s three most effective battleships, the venerable HMS Hood (Captain Ralph Kerr, CBE, RN), the largest warship afloat, HMS King George V (Captain Wilfred R. Patterson, CVO, RN) the new fleet flagship, and HMS Prince of Wales (Captain John Catterall Leach, MVO, RN) still fitting out, the fleet currently contained not a single aircraft carrier.

The newest addition to the Royal Navy’s carrier force, HMS Victorious, having been commissioned on 15 May 1941 under Captain Henry C. Bovell, RN, was currently at Liverpool preparing for her shakedown cruise. There being a war on, even shakedowns involved a mission. Plans had already been set in motion for Victorious to deliver 48 RAF Hurricane IIs to Gibraltar and hence to the beleaguered island of Malta. At the same time, Victorious embarked two Fleet Air Arm organizations to handle fighter and anti-submarine defense of the ship en-route: 800Z Flight with six Fulmar II fighters, and 825 Squadron with nine brand new Swordfish Is, three of which were equipped with the newest in strike technology, Anti-Surface-Vessel (ASV) radar. Bigger things were on tap in the Mediterranean for 825 Squadron, which was slated to replace the long serving 820 Squadron as one of HMS Ark Royal’s Torpedo-Spotter-Reconnaissance squadrons. For 800Z Flight, the job was much more mundane; they were simply ferrying new replacement fighters for Ark Royal’s two fighter squadrons, after which the pilots were scheduled to lead the RAF fighters on to Malta.

HMS Victorious actually embarked 800Z Flight on 11 May. Eight days later, as she moved into the Clyde, 825 Squadron flew aboard. On the 20th the final preparations seemed to be in place when she embarked the 48 RAF fighters. Then fate intervened. Early on the 21st, RAF reconnaissance aircraft had placed the two German warships at Korsfjord near Bergen, Norway, and all indications were that they intended to break out momentarily. As such, Captain Bovell was ordered to disembark the RAF fighters and proceed to Scapa Flow forthwith to join the Home Fleet. On arrival, Admiral Tovey personally interviewed the commander of 825 Squadron, Lieutenant-Commander(A) Eugene Kingsmill Esmonde, RN, as to his squadron’s ability to deliver a torpedo attack. Only after Esmonde satisfied him that the squadron’s training level was satisfactory did Tovey consent to add Victorious to his force, which consisted of the battleship HMS King George V (F), the four cruisers of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron under Rear Admiral Alban T. B. Curteis, CB, RN, HMS Galatea (F), HMS Aurora, HMS Kenya, HMS Hermione, and six destroyers, HMS Active, HMS Punjabi, HMS Nestor, HMS Inglefield, HMS Intrepid, and HMS Lance. Along the way he would be joined by the battlecruiser HMS Repulse (Captain William G. Tennant, CB, MVO) as well.

The spectacular events of the next 72 hours were to prove to be a nadir for the Royal Navy. The RAF confirmed the breakout on 22 May, followed, less than 24 hours later by the dramatic discovery of the force in the Denmark Strait by HMS Suffolk and later HMS Norfolk, flying the flag of the commander of the 1st Cruiser Squadron, Rear-Admiral William Frederick Wake-Walker, CB, OBE, RN. On the morning of 24th, the Home Fleet’s Battlecruiser Squadron, under Vice-Admiral Lancelot Ernest Holland, CB, RN, flying his flag on HMS Hood, along with HMS Prince of Wales and six destroyers, HMS Electra, HMS Anthony, HMS Echo, HMS Icarus, HMS Achates, and HMS Antelope managed to “corner the fox”, but soon found that the this fox had teeth. At 0601, only minutes into the fight, the great flagship blew up. Minutes later, at 0613, Captain Leach was forced to withdraw Prince of Wales under the cover of smoke.

Prelude - HMS Victorious.

Throughout the remainder of the morning and afternoon, while Rear-Admiral Wake-Walker shadowed Lütjens with his own cruisers and Prince of Wales, Admiral Tovey strove to cut off the German squadron with the remainder of the Home Fleet. As the morning turned into afternoon, he decided to hold Esmonde to his word and, at 1509, detached Victorious, escorted by Rear-Admiral Curteis’s four cruisers, to forge ahead, close on Bismarck, and deliver a torpedo attack in a further effort to slow the quarry down. Although Victorious’ Commander Flying, Commander Herbert Charles Ranald, RN, desired the distance closed to 100 miles before launch, Victorious could not get inside 120 miles in the high-seas, and finally, at 2210, all nine Swordfish of 825 Squadron set off on the mission assigned, organized in three sub-flights thus:

| Sub-Flight | Aircraft | Pilot | Observer | TAG | Result |

| 1st | (5)A+ | Lt.Cdr.(A) E. K. Esmonde, RN | Lt. C. C. Ennever, RN | PO(A) S. E. Parker, RN Fx.76360 | port beam |

| 1st | (5)C | S-Lt.(A) J. C. Thompson, RN | A/S-Lt. R. L. Parkinson, RN | PO(A) A. L. Johnson, RN D/Jx.146558 | port bow |

| 1st | (5)B | Lt. N. G. MacLean, RNVR | T/S-Lt.(A) L. Bailey, RNVR | NA D. A. Bunce, RN, SFx.631 | port |

| 2nd | (5)F+ | Lt. P. D. Gick, RN | S-Lt.(A) V. K. Norfolk, RN | PO(A) L. D. Sayer, RN Fx.76577 | port side; bow |

| 2nd | (5)G | T/Lt.(A) W. F. C. Garthwaite, RNVR | T/S-Lt.(A) W. A. Gillingham, RNVR | LA H. T. A. Wheeler, RN Fx.189404 | starboard bow |

| 2nd | (5)H/V4337 | S-Lt.(A) P. B. Jackson, RN | A/S-Lt. D. A. Berrill, RN | LA F. G. Sparkes | starboard quarter |

| 3rd | (5)K | Lt.(A) H. C. M. Pollard, RN | T/S-Lt.(A) D. M. Beattie, RNVR | LA P. W. Clitheroe, DSM, RN P/Jx.135706 | port quarter |

| 3rd | (5)L | T/S-Lt.(A) R. G. Lawson, RNVR | A/S-Lt. F. L. Robinson, RN | LA I. L. Owen | port quarter |

| 3rd | (5)M | S-Lt.(A) A. J. Houston, RNVR | T/S-Lt.(A) J. R. Geater, RNVR | PO(A) W. J. Clinton, RN | did not find Bismarck |

As soon as they were airborne the Swordfish disappeared into a rain squall and were lost to view, but the squadron was able to form up without too much difficulty and set off on a course of 225º. Meanwhile, at 2300, three Fulmars of 800Z Flight followed with orders to observe the attack and then maintain contact at all costs so that, if necessary, another strike could be flown off the next day at dawn. The faster Fulmars soon overtook the lumbering Swordfish, and the combined force continued towards Bismarck at 85 knots.

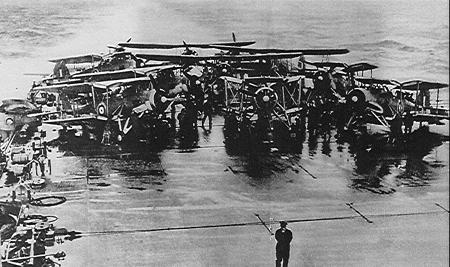

several hours before launch. All nine Swordfish of 825 Squadron are clearly visible as well as, in the extreme rear,

two Fulmars from 800Z Flight.

Realistically, the prospects for the attack were not good. The squadron was ill-prepared for its assignment, several of the pilots having only made their first carrier landing on the 19th, and they had not made even a single squadron attack in training. Under the prevailing weather conditions, eight-tenths cloud cover at 1,500 feet with intermittent rain squalls, a visual search was like looking for the proverbial ‘needle in a haystack’, but the squadron’s new ASV radar was expected to make the difference. At 2327 ASV contact was established on a contact some 16 miles ahead of the formation and Bismarck was sighted briefly through a gap in the clouds only to be lost again seconds later. Descending below the clouds with his squadron, Esmonde located the cruisers still shadowing, and HMS Norfolk directed the aircraft towards their target some fourteen miles ahead on the starboard bow.

At 2350 hours a further ASV contact was made and Esmonde again led his squadron below the cloud cover to begin his attack. Unexpectedly, the contact proved to be the United States Coast Guard cutter Modoc, peacefully pitching and rolling in the heavy Atlantic swell. Unfortunately Bismarck, then only six miles to the south, spotted the aircraft and the vital element of surprise was lost. When the Swordfish finally closed to deliver their torpedo attack, they were met by a ‘very vigorous and accurate’ barrage of heavy and light AA, which tagged Esmonde’s Swordfish (5A) at a range of four miles. Though Swordfish 5M lost contact in the dense cloud covering the area, the remaining eight aircraft pressed home their attack with elan.

At exactly midnight Esmonde led the first sub-flight into a simultaneous attack. His starboard lower aileron was hit almost immediately, and he abandoned his original intention to attack from starboard, deciding to drop there and then, whilst he was still in a good position on the target’s port beam and Bismarck was nicely silhouetted against the glow of the setting sun. Both he, and Sub-Lieutenant(A) Thompson, in 5C, released on Bismarck’s port bow from an altitude of 100’. The third member of the flight, Lieutenant MacLean, in 5B, got separated in the descent through the clouds and attacked separately, but also on the port side. Proving that his ship handling skills were superb, Captain Lindemann artfully dodged all three “fish”.

The three Swordfish of the second sub-flight were led in by Lieutenant Gick. Approaching from starboard, he was not satisfied with the approach angle, and elected to pull back into the clouds and work his way round to a better position. The remainder of his flight continued on however, Lieutenant (A) Garthwaite in 5G dropping on Bismarck’s starboard bow and Sub-Lieutenant(A) Jackson, in 5H/V4337 from her starboard quarter, but again Lindemann avoided the deadly missiles.

Moments later, the two Swordfish remaining in the third sub-flight appeared on the Bismarck’s port quarter, and amid a hail of AA fire, Lieutenant(A) Pollard, in 5K, and Sub-Lieutenant(A) Lawson, in 5L released from a good angle but, again, to no avail. Meanwhile, Percy Gick, in 5F, now appeared low down on the water on the enemy’s port bow. His sudden appearance caught the Germans by surprise, and there was no avoiding his torpedo, which plowed into Bismarck amidships, exploding on her armour belt.

As the aircraft turned away, the air gunners sprayed Bismarck’s superstructure and gun positions with .303 machine gun fire at almost point blank range. As one of the air gunners remarked later: “It didn’t sink the Bismarck, but it certainly kept their heads down and in any case, it relieved our feelings.” As the Swordfish departed, Petty Officer Airman Parker, Esmonde’s TAG, signaled “Have attacked with torpedoes. Only one observed.” A German account of the attack is summarized from an eyewitness report and states:

-

“They came in flying low over the water, launched their torpedoes and zoomed away. Flak was pouring from every gun barrel but didn’t seem to hit them. The first torpedo hissed past 150 yards in front of the Bismarck’s bow. The second did the same and the third. Helmsman Hansen was operating the press buttons of the steering gear as, time and time again, the Bismarck maneuvered out of danger. She evaded a fifth and then a sixth, when yet another torpedo darted straight towards the ship. A few seconds later a tremendous shudder ran through the hull and a towering column of water rose at Bismarck’s side. The nickel-chrome-steel armor plate of her ship’s side survived the attack ...”

The single hit was confirmed by a shadowing Fulmar who, just after midnight, reported a “great, black column of dense smoke rising from the starboard side”, and also that “the battleship's speed was reduced”. At this point, relief was in order for the three Fulmars over Bismarck, so at 0100 Victorious launched a further pair to relieve those on duty and continue shadowing Bismarck until dawn. The crews of these two aircraft were:

| Sqn | Aircraft | Pilot | Observer | Result |

| 800Z | ? | Lt.(A) Brian Donald Cambell, RN | T/S-Lt.(A) Matthew Gordon Goodger, RNVR | FTR |

| 800Z | ? | Lt. Francis Charles Furlong, RNVR | S-Lt. John Edward Melvill Hoare, RNVR FL at sea; | rescued |

This mission proved to be beyond the rookie crews of 800Z Flight. Operating at night, it horrific weather, without radar, the aircraft soon found themselves separated; neither was able to locate their target. Lost at sea, with little hope of survival short of a miracle, both aircraft eventually were forced to settle into the Atlantic. Lieutenant(A) Cambell, RN and Sub-Lieutenant(A) Goodger were slated to join the vast number of Naval personnel missing and presumed lost. Lieutenant Furlong and Sub-Lieutenant Hoare proved much luckier. Left bobbing in the stormy North Atlantic in their small raft for 36 hours, the forlorn pair was ultimately rescued by the SS Beaverhill (GB, 1928, 10,0041 BRT).

Sunset was at 0052 hours, and the returning strike force had to make most of their journey back to HMS Victorious in the dark. With the homing beacon aboard the carrier unserviceable, Captain Bovell, risking the danger from enemy submarines, shone his searchlights vertically upwards onto the clouds to guide the aircraft, until ordered to put them out by Rear-Admiral Curteis. Stubborn to the last, Bovell then signaled his acquiescence with his brightest 20-inch signal projector! None the less, all nine Swordfish found the carrier at 0155 and landed on safely between 0200 and 0230, the returning crews all stating that they had not seen the searchlight display, but had easily sighted and followed the low-intensity signal lamps used by the cruisers! At 0306, just after the last aircraft had landed aboard Victorious, and following a brilliant maneuver by Lütjens, the two shadowing cruisers, HMS Norfolk and HMS Suffolk lost contact with Bismarck. For the next thirty-six hours a vast network of airborne and surface ship searches attempted to locate the elusive enemy.

While Victorious’ strike role was now over, 825 Squadron’s Swordfish were part of the search effort. In the mid-morning of the 25th, three Swordfish were put up, but they had no luck. While two managed to return to Victorious, 5H/V4337 was not so lucky. By 1315 things looked bleak for the three aircrew Sub-Lieutenant(A) P. B. Jackson, RN (P), Acting Sub-Lieutenant D. A. Berrill, RN (O), and Leading Airman F. G. Sparkes (TAG). However, lady luck kept her eye on the trio, for below them, floating on the otherwise empty sea, was an lifeboat! Force-landing alongside and scrambling in, they discovered that it was fully stocked with water and provisions! Meanwhile, Victorious conducted a search for her missing craft, but when it came up empty, the crew was presumed lost. However, eight days later, on 3 June, the Icelandic steamer Lagufoss (ex. Profit, 1904, 1,211 BRT) came across the three 50 nautical miles E of Cape Farewell, little worse for their unexpected dunking!

A further effort on the 26th, again by three aircraft, proved more costly. This time the missing Swordfish simply disappeared. Lost with it were three of the men that attacked Bismarck 30 hours earlier: Lieutenant(A) Henry Charles Michell Pollard DSC, RN (P-age 24), Sub-Lieutenant(A) David Musk Beattie, RNVR (O-age 24), and Leading Airman Percy William Clitheroe, DSM, RN (TAG-age 25).

Thus ended HMS Victorious’ role in the hunt for the Bismarck. On 16 September, awards were posted in the London Gazette for the aircrew who had participated in the hunt. 825’s commanding officer Lieutenant-Commander Esmonde was awarded the DSO. DSCs went to Lieutenants Gick and Ennever, Lieutenants(A) Garthwaite and the missing Pollard, and Sub-Lieutenant Norfolk. Three of the air gunners, Petty Officer(A) Parker, and Leading Airmen Johnson and Sayer were awarded the DSM. Finally, Sub-Lieutenants Bailey, Berrill, and Lawson were Mentioned in Dispatches. On 14 October, Victorious’ Commander Flying Commander Ranald was awarded the OBE.

As a final footnote, 24 May did not mark the last time 825 Squadron would attack a German battleship. Some nine months later, on 12 February 1942, during the Channel dash, six Swordfish of a reformed 825 Squadron, still led by the indomitable Esmonde, would fly on a one-way mission to destiny. Among the 13 airmen killed that day were six of the 24 survivors of the Bismarck attack:

| Lieutenant-Commander(A) Eugene Kingsmill Esmonde, DSO, VC, RN (P) | age 32 | Swordfish W5984/H |

| Petty Officer Airman William Johnson Clinton, RN (TAG) | age 22 | Swordfish W5984/H |

| Petty Officer Airman Ambrose Lawrence Johnson, DSM, RN (TAG) | age 22 | Swordfish W5983/G |

| Sub-Lieutenant(A) John Chute Thompson, RN (P) | age 27 | Swordfish V4523/F |

| Sub-Lieutenant Robert Laurens Parkinson, RN (O) | age 21 | Swordfish W5985/K |

| Leading Airman Henry Thomas Albert Wheeler, RN (TAG) | Swordfish W5985/K |

Seven months later, on 17 September, 1942, the survivors were reduced yet again when Sub-Lieutenant(A) Valentine Kay Norfolk, DSC, RN (O), was killed in Swordfish DK776 while a member of 816 Squadron.

As far as I have been able to determine, the remaining seventeen survived World War II, all members of an extremely unique fraternity. I do know that Lieutenant-Commander Percy David Gick, RN became the OC of 815 Squadron, FAA on 14 December 1941.

Finale - HMS Ark Royal.

Even before the Bismarck crisis had begun, important events were transpiring in the Western Mediterranean. On 12 May, HMS Furious had departed Greenock under the protection of HMS London, and sailed for Gibraltar carrying 40 RAF Hurricane IIs and nine FAA Fulmar IIs of the new 800X Flight, the lot being destined for Malta. Arriving on the 18th, the 19th was spent transferring 21 of the Hurricanes and all of the Fulmar IIs (exchanged for worn out Fulmar Is) to HMS Ark Royal. On the 20th, Force H, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir James Fownes Somerville KCB, DSO, RN, flying his flag on the battlecruiser HMS Renown (Captain Rhoderick R. McGriggor), sortied into the Western Mediterranean with the two carriers, cruiser HMS Sheffield, and six destroyers, HMS Faulknor, HMS Foresight, HMS Forester, HMS Foxhound, HMS Fury, and HMS Hesperus, to begin Operation “Splice”.

On the 21st, amid significant confusion, seven Fulmars and 48 Hurricane I/IIs departed for Malta. While two Fulmars and one Hurricane were lost en-route, the rest reached Malta safely. Turning about, Force H returned to Gibraltar on the 22nd. For the next 48 hours, the news about the Bismarck’s break out captured the world’s imagination. Then, just before the Victorious’ attack commenced, at 2331 on the evening of 24th, the Admiralty signaled Vice-Admiral Somerville to again take Force H to sea and “Steer so as to intercept Bismarck from southward. Enemy must be short of fuel and will have to make for an oiler. Her future movements may guide you to this oiler.”

Leaving Furious behind (as she carried no aircraft), Somerville led Force H into the Atlantic. HMS Ark Royal (Captain Loben E. H. Maund, RN) was carrying five Fleet Air Arm Squadrons, believed to total 23 Fulmar I/II fighters and 27 Swordfish I TSRs:

| 807: | 11 x Fulmar I/II | Lieutenant-Commander James Sholto Douglas DSO, RN |

| 808: | 12 x Fulmar II | Lieutenant-Commander Rupert Claude Tillard, RN |

| 810: | 9 x Swordfish I | Lieutenant-Commander Mervyn Johnstone DSC, MiD, RN |

| 818: | 9 x Swordfish I | Lieutenant-Commander Trevenen Penrose Coode, RN |

| 820: | 9 x Swordfish I | Lieutenant-Commander James Andrew Stewart-Moore, RN |

As British forces combed the most likely routes open to Bismarck, an official Admiralty communiqué told an anxiously waiting world the outcome of events thus far:

-

“After the engagement yesterday in the North Atlantic, the enemy forces made every effort to shake off the pursuit. Later in the evening an attack by naval aircraft resulted in at least one torpedo hit on the enemy. Operations are still proceeding with the object of bringing the enemy forces to close action.”

Admiral Lütjens was obviously impressed by the fact that British radar had enabled the two cruisers to keep contact with her for a night and a day, in darkness and very bad weather. At 0401 on the morning of the 25th, unaware that at last he had in fact given them the slip, he proceeded to send a long signal to Group West to outline his view of events thus far:

-

“Enemy radar gear with a range of at least 35,000 meters interferes with operations in Atlantic to considerable extent. In Denmark Strait ships were located and enemy maintained contact. Not possible to shake off enemy despite favorable weather conditions. Will be unable to oil unless succeed in shaking off enemy by superior speed . . .”

Unable to interrupt the transmission, it was not until 0846 that Group West was able to signal Lütjens that it was their belief that contact had been lost some six hours earlier! Lütjens immediately resumed radio silence, but the damage had been done. All through the 25th and 26th Victorious continued to fly off her Swordfish on anti-submarine patrols and air searches, but nothing was found. At 1625 on the 25th Adolf Hitler sent a personal message to Admiral Lütjens offering, ‘Best wishes on your birthday’. It was not acknowledged as Bismarck kept silent, steaming at a reduced speed of 20 knots for the safety of a French West Coast port. She was running short of fuel due to the hit on her oil tanks and at one point, was reduced to 12 knots to allow for repairs to her damaged forecastle. (Had Bismarck been able to travel at her full capability of 28 knots throughout, there is little doubt that she would have made that port she sought). At 1924 the Admiralty informed all ships their belief that Bismarck was making for western France.

That night, Force H steamed northwards into an increasingly heavy sea and a rising wind. With waves reaching more than 50 feet, Somerville was forced to reduce his speed; first to 23 knots at 2115, to 21 knots at 2340, 19 knots at 0000, and finally to 17 knots at 0112. At dawn on 26th, even HMS Ark Royal, with her deck 62 feet above the water, was “taking it green”, and the wind over the flight deck had reached 50 knots.

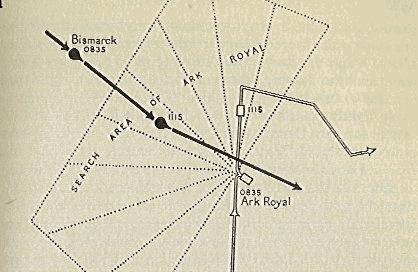

Dawn saw Coastal Command renew the aerial search with vigor. At 0835 Ark Royal joined the effort by launching 10 Swordfish to search the western semicircle, covering the 180o arc from south-southwest through north-northeast. At half past ten that morning, Pilot Officer Dennis A. Briggs, RAF, (carrying Ensign Leonard B. “Tuck” Smith, USN as co-pilot) flying Catalina Z of 209 Squadron from Lough Erne, Ireland, on the southernmost of the Bay patrols, sighted Bismarck. Although Bismarck immediately engaged the stranger with heavy and accurate fire, the Catalina was able to get off a fairly accurate sighting report before losing the battleship in the weather. His position report placed Bismarck 690 miles to the west-northwest of Brest and gave the pursuers less than 24 hours in which to intercept, after which she would reach the friendly umbrella of protection afforded by the Luftwaffe, and ultimately the sanctuary of port. Admiral Tovey’s only hope was to slow her down with yet another air strike, and the only carrier within striking distance was HMS Ark Royal coming up from the south.

Copying Briggs contact report, the two closest Swordfish altered course to intercept. At 1114, 2H (Sub-Lieutenant(A) J. V. Hartley, RN, Acting Sub-Lieutenant P. R. Elias, RNVR Leading Airman H. F. Huxley, RN SFx.899) sighted what they believed was a German cruiser. Seven minutes later 2F (Lieutenant(A) J. R. C. Callander, RN, Lieutenant P. B. Schondfeldt, RN, and Leading Airman R. Baker) joined 2H and identified Bismarck. Meanwhile, Ark Royal fitted two ASV-equipped Swordfish with long-range tanks and sent them off at 1200 to maintain contact until relieved. At 1154 Bismarck broke her long silence, reporting that she was being shadowed by an enemy 'Land plane'. Thereafter, and until 2320 that night, Ark Royal’s Swordfish, working in pairs, maintained a vigil over Bismarck, keeping her under continuous observation.

26 May 1941. |

Beginning sometime after noon, Ark’s search planes began fluttering home; the last two were 2F and 2H, coming aboard at 1324. With the search planes safely aboard, the flight deck personnel began the daunting job of preparing the critical torpedo striking force to hit the enemy in conditions that bordered on the horrific. Eventually, fourteen Swordfish from all three TSR Squadrons, each armed with an 18” torpedo, were ranged. Meanwhile, in a further effort to maintain contact, Vice-Admiral Somerville ordered HMS Sheffield to close Bismarck and to shadow her with radar. In what would turn out to be a glaring omission, HMS Ark Royal was not informed of this action.

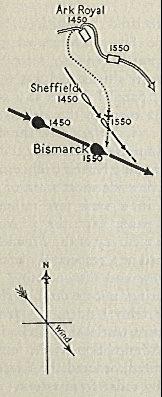

At 1450, after a meticulous briefing during which the strike commander, Lieutenant-Commander J. A. Stewart-Moore, was specifically informed that only Bismarck was in the target area, the 820 Squadron Officer Commanding (OC) led the strike off. At 1520, the strike group detected a target on ASV radar; some twenty miles closer than expected. Knowing that only Bismarck herself was in the target area, Stewart-Moore began his attack approach and, at 1550, the Swordfish burst out of the bottom of the cloud cover and commenced their attack. It was readily apparent that they had totally surprised their foe, as there was quite literally, no AA fire. With devastating swiftness the Swordfish descended from all points of the compass dropping their deadly cargoes. Only after 11 had released did the true reason for the lack of defensive fire become apparent; they were attacking HMS Sheffield!

Realizing that it was a case of mistaken identity and to his eternal credit, Sheffield’s commanding officer, Captain Charles A. A. Larcom, RN, ordered his guns to “on no account fire”. Then, ringing down to the engine room for full speed, he calmly conned the ship through the dangerous waters, successfully dodging the six torpedoes that came his way. Of the other five torpedoes, two exploded when they entered the water and three exploded in Sheffield’s wake.

One Swordfish, recognizing Sheffield after dropping, made a signal to her, ‘Sorry for the Kipper’, as they turned for home, still facing the challenge of returning safely whence they had come. Landing conditions had become even worse than before, and the Deck Control Officer had to attach a rope to his waist before he could stand back to the wind, holding up the ‘bats’. Three aircraft crashed on the flight deck as they came on, the rising stern smashing their undercarriages, and the wreckage had to be cleared away before the others could be taken on. Fortunately, there were no crew casualties, and all were aboard by 1720. None the less, they were a crestfallen band.

Although it was immediately questioned whether further air operations were even possible in the steadily worsening weather, the aircrews were adamant in their desire to have another go. Over the next 90 minutes the flight deck personnel again struggled to get the available aircraft armed, fueled, and onto the pitching flight deck. By 1900, Ark Royal began turning into the 50 knot wind, the last fifteen airworthy Swordfish, four from 810, four from 818, and seven from 820 were ranged on deck and the aircrews began manning their planes.

| Flight | Sqn | Aircraft | Pilot | Observer | TAG | Result |

| 1st | 818 | 5A/ P4219? | Lt.Cdr. T. P. Coode, RN | Lt. E. S. Carver, RN | PO W. H. Dillnutt | port beam |

| 1st | 818 | 5B+ | T/S-Lt.(A) E. D. Child, RNVR | S-Lt.(A) G. R. C. Penrose, RN | LA R. H. W. Blake | port beam |

| 1st | 818 | 5C/L9726 | T/S-Lt. J. W. C. Moffatt, RNVR | T/S-Lt.(A) J. D. Miller, RNVR | LA A. J. Hayman, Jx.151230 | port beam, hit stern |

| 2nd | 810 | 2B+ | Lt. D. F. Godfrey-Faussett, RN | S-Lt.(A) L. A. Royall, RN | PO(A) V. R. Graham, F.55072 | starboard |

| 2nd | 810 | 2A+/ P4131? | S-Lt.(A) K. S. Pattisson, RN | S-Lt.(A) P. B. Meadway, RN | NA D. L. Mulley | starboard beam |

| 2nd | 810 | 2P | S-Lt.(A) A. W. D. Beale, RN | A/S-Lt.(A) C. Friend, RN | LA K. Pimlott, RN SFx.392 | port bow - hit amidships |

| 3rd | 818 | 5K | Lt.(A) S. Keane, DSC, RN | S-Lt.(A) R. I. W. Goddard, RN | PO(A) D. C. Milliner Fx.77749 | with 1st sub-flight |

| 3rd | 810 | 2M | S-Lt.(A) C. M. Jewell, RN | - | LA G. H. Parkinson | with 4th sub-flight |

| 4th | 820 | 4A | Lt. H. de G. Hunter, MiD, RN | Lt.Cdr. J. A. Stewart-Moore, RN | PO(A) R. H. McColl, DSM, Fx.76319 | port side |

| 4th | 820 | 4B | S-Lt.(A) M. J. Lithgow, RN | T/S-Lt.(A) N. C. M. Cooper, RNVR | LA J. Russell | port side |

| 4th | 820 | 4C/V4298+ | S-Lt.(A) F. A. Swanton, RN | T/S-Lt.(A) G. A. Woods, RNVR | LA J. R. Seafer | port side; a/c jettisoned |

| 5th | 820 | 4K/ L7643? | Lt.(A) A. S. S. Owensmith, RN | A/T/S-Lt.(A) G. G. Topham, RNVR | PO J. Watson, Fx.76318 | starboard side |

| 5th | 820 | 4L/ P4204? | S-Lt.(A) J. R. N. Gardner, RN | T/S-Lt.(A) J. B. Longmuir, RNVR | - | jettisoned |

| 6th | 820 | 4F | S-Lt.(A) M. F. S. P. Willcocks, RN | S-Lt. H. G. Mays, RN | LA R. Finney, Jx.156354 | jettisoned |

| 6th | 820 | 4G | S-Lt.(A) A. N. Dixon, RN | T/S-Lt.(A) J. F. Turner, RNVR | LA A. T. A. Shields | starboard |

This time the air staff had put together an improved plan of attack. First, because of the premature explosions of virtually half the torpedoes on the previous attack, the new duplex (magnetic) pistols that had been used were discarded and replaced by older, but reliable, contact pistols. Second, the new strike commander Lieutenant-Commander T. P. Coode, OC of 818 Squadron, was briefed to led the group directly to Sheffield, maintaining her vigil some 12 miles astern of Bismarck, get a fresh bearing to the target, and then attack. The crews realized the importance of their task. They, and they alone, could stop the Bismarck from reaching the safety of Brest, for it was certain that the Fleet could not possibly catch up if the Fleet Air Arm Swordfish did not slow the German battleship down.

One can imagine that scene: the fifteen Swordfish ranged on the pitching flight deck, wing-tip to wing-tip; the tumultuous roar from the exhausts; the flurries of spray beating on the linen covered fuselages; the aircrews bundled in their wool-lined flight suits damp with spray; the ratings at the chocks bracing their bodies against the drive of the wind; the lead plane taxies into the center of the deck; the Pegasus engine roaring at full power as the brakes strain too hold the airframe stationary. Then, at 1910, the Flight Deck Officer waves his green flag, the pilot lets off the brakes and shifts he feet to the rudder pedals and the first Swordfish begins moving forward, racing down the deck and rising into the surrounding gale.

|

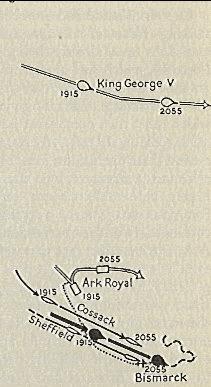

The group formed up over Somerville’s flagship and took their departure at 1925. A little more than a half hour later Sheffield was sighted, and she blinkered them to proceed on a bearing of 110º, distance 12 miles. Conditions were less than ideal, with seven-tenths cloud cover extending from 2,000-5,000 feet and as Coode climbed for altitude he lost Sheffield. The group was forced to orbit the area, slowly decreasing altitude, looking for a break in the clouds to relocate the cruiser until finally, at 2035, Coode relocated his guide. Armed with a new fix, the group completed its climb to 6,000 feet and, at 2040, disappeared into the gray mist at 110 knots, in sub-flights in line astern formation.

Lieutenant-Commander Coode (5A) had planned a coordinated attack with the sub-flights coming in simultaneously from different angles, forcing Bismarck to divide her fire and making it harder for her to evade torpedoes. With no sign of a break in the cloud cover - down to 2,000 feet - the chances of reforming were slender, so each sub-flight was ordered to return independently.

Thirteen minutes after leaving Sheffield, Coode estimated that they should be in a good position and started the dive. Coode later reported ‘Visibility was limited - a matter of yards. I watched the altimeter go back. When we reached 2,000 feet I started to worry. At 1,500 feet I wondered whether to continue the dive. At 1,000 feet I felt sure something was wrong, but still we were completely enclosed by cloud. I held the formation in the dive, and at 700 feet only we broke cloud, just when I was running out of height.’ The time was 2055.

Most of the striking force became split up in the thick blanket of cloud, and they went in to the attack as best they could; in pairs, threes, fours, or even alone. The Commander-in-Chief stated afterwards that the attacks were pressed home ‘with a gallantry and determination which cannot be praised too highly’.

Coode found he was four miles ahead and to leeward of the target. Realizing that a slow approach against the wind would be suicidal, he re-entered the cloud to close in and try another angle. This left the second sub-flight, to ‘open the ball’. Lieutenant D. F. Godfrey-Faussett (2B) having lost Coode in the clouds, led the second sub-flight up to 9,000 feet where they ran into some icing problems before descending on the ASV’s attack bearing. He and Sub-Lieutenant(A) K. S. Pattisson (2A) were both caught in an intense AA barrage that hit both aircraft as they made their run in from the Bismarck’s starboard beam, but both survived the storm of ‘shot and shell’. Meanwhile, Sub-Lieutenant(A) A. W. D. Beale (2P) having lost touch with the other two, returned to Sheffield to get a new range and bearing to the enemy. Of him and 2P we’ll hear more later.

The third and fourth sub flights managed to stay together in the descent until they hit 2,000 feet, then they separated. As they cleared the clouds, four, Lieutenant H. de G. Hunter (4A), and Sub-Lieutenants(A) M. J. Lithgow (4B), F. A. Swanton (4C), and C. M. Jewell (2M) reformed in a clear patch of sky as they popped out of the underside of the cloud layer, and forged in from the port side at the same time as the second sub-flight came in from starboard. The German flak was extremely accurate, and followed them until they were seven miles from the target. Bismarck’s gunners seemed to be particularly attentive to 4C, which tallied no less than 175 holes in it. Both the pilot, Sub-Lieutenant(A) Swanton and his TAG, Leading Airman J. R. Seager were wounded, while the observer, Sub-Lieutenant(A) G. A. Woods weathered the storm unscathed.

Separated from the others, Lieutenant(A) S. Keane, DSC (5K), leader of the third sub-flight tagged on to Coode’s sub-flight as they closed in. They popped out on the target’s port beam and immediately came under intense and accurate AA fire which hit, but did not bring down 5B, piloted Sub-Lieutenant(A) S. D. Child. As they withdrew, Keane’s crew reported that they saw a hit on Bismarck’s starboard side near the funnel. While the actual location was considerably further aft (and on the other side!), they were apparently eyewitnesses to one of the most decisive blows in modern history as, at 2105, the torpedo released by Sub-Lieutenant J. W. C. Moffatt (5C) struck the extreme stern of the target.

The fifth sub-flight lost each other in the clouds. As the leader, Lieutenant(A) A. S. S. Owensmith (4K), descended through the clouds at 3,000 feet he found himself the subject of intense AA fire, apparently controlled by radar. Breaking out at 1,000 feet, he found himself badly placed astern of the target, and so began to work around into a more favorable angle on her starboard side. While doing so, he saw a large plume of water rise up right aft from Bismarck’s port side. Left with the impression that he was ‘flying through a wall of smoke and water’ Owensmith noted that Bismarck was swinging around to port which seemed to be an extremely odd form of avoiding action to be taking given his angle of approach. Meanwhile Sub-Lieutenant(A) J. R. N. Gardner (4L) made two separate attempts to close, but was met with such a concentration of fire that he was forced to withdraw.

Meanwhile the sixth sub-flight climbed to 7,450 feet where they broke the clouds. Disorientated, they too returned to HMS Sheffield, received a new range and bearing, and forged ahead again. Diving to attack on Bismarck’s starboard side, they found themselves subjected to the combined fire of her entire flak battery. Sub-Lieutenant(A) A. N. Dixon (4G), was forced to release some 2,000 yards out. His leader Sub-Lieutenant(A) M. F. S. P. Willcocks (4F), having thoughts of making another approach, retained his.

While all this was transpiring, 2P, flown by the indomitable Sub-Lieutenant(A) A. W. D. Beale reappeared ahead of Bismarck on her port bow, and attacked alone. In spite of the very intense and accurate fire he was rewarded by an enormous column of smoke and water that rose up on the port side of Bismarck’s deck as, at 2115, their torpedo hit home.

By this point, all the Swordfish had had at least one go at the target and 13 were on their way home. This left two, Gardner in 4L and Willcocks in 4G still striving to get in close enough to make a reasonable drop. However, as the remainder withdrew, they found themselves under extremely accurate flak at every turn, even when they lost sight of the their quarry. Finally, both were forced to face the realization that further attempts were simply suicidal and they too turned about, jettisoned their torpedoes, and headed home. By 2125, the attack was over.

Such were the difficulties of observation that Coode reported immediately after the attack that he did not think the Bismarck had suffered any significant damage. As the Swordfish streamed home, HMS Sheffield’s radar plot noted that Bismarck was maneuvering erratically, and began to close in an effort to ascertain if Bismarck had, if fact, been damaged. At 2140 she poked out of the broken mist and found herself subjected to six well aimed salvos of 15” shells. Humbled in the extreme, Captain Larcom hastily withdrew having determined that her fighting efficiency had not diminished!

At 2205, the first Swordfish began returning to Ark Royal. As the observers made their individual reports, it became clear that the results were more successful than first supposed, and it was first established that the Bismarck had been hit on the port side, then on the starboard quarter. Later still a possible hit on the port quarter was reported.

At 2300, the last of the strike planes was aboard. It had been an interesting recovery. The weather was still abominable, and five of the attacking Swordfish had been hit by the AA fire. Swanton managed to get back on to Ark Royal in one piece, but on closer inspection 4C was found to be damaged beyond repair and it was jettisoned. Three others crashed on landing, but miraculously no one was hurt. Only six of the Swordfish remained serviceable and, expecting the possibility that another attack would be necessary, they were re-armed and ranged for yet another strike.

Even as the last of the aircrew headed for the ready room for debriefing, the damage was confirmed by a signal from the shadowing Swordfish that Bismarck had made two circles at slow speed and was staggering off to the north-north west. The impossible had really occurred. Unbelievably, at the proverbial eleventh hour, those gallant young airmen, the Fleet Air Arm’s own dashing ‘few’, had actually crippled Germany’s great battleship!

At 2320, after nearly five hours in the air, the two Swordfish shadowing Bismarck were recalled. With Bismarck steering back on her pursuers, apparently unmanageable, and with the destroyers of Captain Phillip Vian DSO, RN’s 4th Destroyer Flotilla on hand, the Fleet Air Arm’s role in the hunt was coming to a close. They came aboard at 2345, just before nightfall.

By dawn on the 27th, the weather was, if anything, worse. Admiral Tovey closed in with HMS King George V and HMS Rodney and, at 0847, the final battle began. Realizing that further torpedoes would probably be needed to actually sink Bismarck, Ark Royal’s flight deck personnel strove to range a strike group made up off all of her serviceable Swordfish.

At 0900, sounds of heavy gunfire could be heard, even over the cry of the wind. Twenty minutes later Ark turned into the wind and, with a 56 knot wind over the deck, launched the twelve plane strike. They sighted the foe, now but a battered hulk, at 1020, but were unable to attack as the shells from the British battleships were falling all around her. Then, as they circled overhead, HMS Dorsetshire closed in and circled Bismarck, firing torpedoes from both sides. Finally, at 1036, the great ship capsized and sank. Having had a “ring side seat” for one of history’s great events, they turned and headed home, the hunt over.

On 16 September, awards were posted in the London Gazette for the aircrew who had participated in the hunt. Strike leader Lieutenant-Commander Coode was awarded the DSO. DSCs went to Lieutenants Carver, Godfrey-Faussett, and Hunter, Sub-Lieutenant Elias, for his expert navigation while shadowing Bismarck, and Sub-Lieutenant(A) Beale. For his excellent work on the radio while shadowing Bismarck, Leading Airman Huxley was awarded the DSM. In January 1942 the Gazette posted a further DSC for Sub-Lieutenant(A) Pattisson, while Lieutenant(A) Keane, DSC was Mentioned in Dispatches.

As a final footnote, although the war raged for four more years, for most of the 43 men from Ark Royal that attacked Bismarck the war seems to have been kind; 35 were destined to survive the war. However, eight were to lose their lives.

On 1 August 1941, after 810 Squadron delivered an attack on Alghero airfield, one of the returning Swordfish crashed while landing on HMS Ark Royal, detonating a 40 pound bomb that had hung up in its rack. Included in the five fatalities caused were Lieutenant(A) Clive Morton Jewell, RN, age 25 and the Sub-Lieutenant(A) Lionel Arthur Royall, RN, age 21.

On 22 September, 1941, Leading Airman Kenneth Pimlott, RN, was a Telegraphist Air Gunner in Swordfish L7660 of 830 Squadron returning to Hal Far after an attempted night strike on a convoy when the aircraft crashed from 500 feet, detonating the torpedo it was still carrying, killing the pilot and fatally injuring Pimlott.

On 24 January 1942, Lieutenant(A) Murry Francis Sanders Peake Willcocks, RN was killed piloting Swordfish V4708 of 812 Squadron out of North Front on an Anti-Submarine Patrol when it suffered an engine failure and crashed in the sea off Gibraltar. He was 26.

On 11 March 1942, Lieutenant David Frederick Godfrey-Faussett, DSC, RN was piloting Swordfish L2772 as a member of 767 Squadron operating from HMS Condor (Arbroath) when it flew into the sea off Easthaven on a night formation flight. He was 28.

Less than a month later, on 5 April 1942, Sub-Lieutenant(A) Anthony William Duncan Beale, DSC, RN was killed as a member of 788 Squadron from China Bay. Flying in line astern formation through the balloon barrage North of Columbo, Ceylon the formation was attacked by IJN A6M2 Zero fighters of the Hiryu kansen Buntai. His Swordfish, V4371 was shot down into the sea. He was 21.

On 5 November 1942, Lieutenant(A) Hugh de Graaff Hunter, DSC, RN was killed piloting Albacore N4357 of 786 Squadron out of HMS Jackdaw (Crail) when it crashed in the Firth of Forth while making an practice torpedo attack. He was 26.

Finally, on 25 January 1943, Commander Trevenen Penrose Coode, DSO, RN, the strike commander on the Bismarck attack, was piloting Martlett AX746 out off HMS Kipanga (Kilindini) when it caught fire and crashed while flying low at night. He was 35.

Of the others, several were to have highly distinguished careers in the Fleet Air Arm.

Lieutenant-Commander James Andrew Stewart-Moore, RN left 818 Squadron to become the OC of 827 Squadron, FAA on 18 July 1941. Promoted to Lieutenant-Commander(A) Stanley Keane became the OC of 825 Squadron, FAA on 23 February 1942. Likewise promoted, Lieutenant-Commander Edmund Squarey Carver DSC, RN became the OC of 826 Squadron, FAA on 15 August 1945.

Francis Alan Swanton, DSO, DSC+bar became the OC of 828 Squadron, FAA as a Lieutenant-Commander on 1 March 1844, commanded 814 Squadron, FAA operating Firefly FR.1s on 17 April 1947, and finally commanded 812 Squadron, FAA, operating Firefly 5s, on 1 March 1951. Lieutenant-Commander(A) Eric Dixon Child, RNVR became the OC of 1792 Squadron (Firefly), FAA, on 15 May 1945. Finally, Lieutenant-Commander Kenneth Stuart Pattisson DSC, RN became the OC of 815 Squadron, FAA, operating Barracuda TR.3s, on 1 December 1947 followed by 810 Squadron, FAA, operating Firefly FR.4s on 17 October 1949.

Epilogue - Just Who Did Hit the Bismarck?

There is considerable confusion in print concerning the number, location, timing, and who it was that actually scored the torpedo hits on Bismarck. Virtually all British sources that I am aware of indicate that the two torpedoes definitely struck. Some, including the official action reports, mention the possibility of a third hit as well. As to location, the few that do so indicate invariably specify that the torpedo that struck the stern did so on the starboard side, while all seem indicate that other hit did so on the port side. The sources seem evenly split as to which hit first. As to who actually scored the hits, the only sources that I am aware of that indicates who scored both hits are Kennedy (Pursuit: The Chase and Sinking of the Battleship Bismarck) and Archbold (The Discovery of the Bismarck) which, assume that the hit on the stern came from the starboard side and give credit to Godfrey-Faussett’s second sub-flight.

On the other hand, based on what I know of the German official report (I have not seen a direct translation of the original) radioed from Bismarck on 26 May categorically states that two torpedoes hit home, the first hitting the stern, though the side of the ship struck is not indicated. The Bismarck survivor accounts that I am aware of all agree in their recollection that all the torpedoes struck the port side. As to the number of hits, they seem fairly split between two and three. As to the actual timing of the hits, Burkard von Müllenheim-Rechberg, Bismarck’s senior surviving officer, is adamant in their belief that, regardless of how many hits were received, the last hit was the one on the stern.

Based on the historical evidence from the attacking flight crews, the survivors, and the only action report available from the German side (Lütjens radioed report), I believe the sequence of events as recorded above is correct. My rationale is as follows:

First, I do not believe that Admiral Lütjens would have erred in either the number of hits or in the timing. It is inconceivable to me that, knowing that his report was likely to be his only opportunity to get the pertinent facts to Group West, that he would have been incorrect in those two most critical facts. Second, I believe that the Germans were in a much better position to know which side of the ship was actually hit, and all the evidence the survivors presented concerning known damage and flooding occurred on the port side. Therefore, my conclusion is that two torpedoes struck Bismarck’s port side on 26 May. But who obtained the hits?

The most critical aspect of this issue is the order in which the various sub-flights actually delivered their attacks. Based on the aircrew reports there is, in my opinion, little doubt that Godfrey-Faussett’s second sub-flight (less Beale), attacking from starboard, and the third and fourth sub-flights (less Keane), attacking from port, attacked before Coode’s sub-flight. The fact that the attack commander did not actually lead the initial aspects of the attack is critical to understanding how the attack actually unfolded.

Coode’s initial reports noted that his crew observed no indication of damage. Clearly then, whatever happened to Bismarck occurred after Coode was well into his withdrawal. Likewise, the action reports leave little doubt that Keane and Owensnith, the first British flight crews to observe damage to Bismarck, attacked after Coode.

Both of these flight crews were highly experienced. Keane had served continuously in 818 Squadron since 1 October 1939, Goddard, his observer, since 27 March 1940. With their Telegraphist Air Gunner Milliner, they had survived the Norwegian Campaign flying from HMS Furious. Owensmith and his observer Topham, having each joined 820 Squadron on 23 February 1940, and the equally long serving Telegraphist Air Gunner Watson had done the same from HMS Ark Royal. Both crews had served continuously on Ark Royal ever since, flying on countless operations.

While Keane’s crew indicates the hit was elsewhere, they attacked immediately after Coode and were well into their withdrawal when they observed a hit. Given the poor visibility and the fact that Keane was taking evasive action during the withdrawal, it is highly likely that the crew only had a fleeting instant to observe the only visible results - the plume caused by the hit. With the aircraft and ship both moving violently, at relatively high speed, in my opinion little more could be accurately observed.

On the other hand, Owensmith, attacking from the opposite side at roughly the same time Coode’s section was turning to withdraw, was definitive that Bismarck reacted strangely to a hit on her port side aft. As he was heading right for her on his attack run, he was in a perfect position to note both the hit and Bismarck’s reaction to it, as his chance of success depended on observing those very reactions. Therefore, I find his observations highly credible.

Furthermore, almost all sources agree that Beale, attacking alone from the forward points of the compass, slipped in virtually unseen and scored the hit amidships. He stated clearly that he encountered no AA fire until after he dropped. Since he had actually returned to HMS Sheffield before making his attack there is, in my opinion, little doubt that he was one of the last attackers. If his torpedo hit, it did so well after Keane and Owensmith were on their way home.

Finally, both the British and German records agree that the attack began around 2055 and lasted roughly a half an hour. Therefore, indications are that both sides were timing events from the roughly same starting point. Lütjens’ report indicates that the first torpedo hit home at 2105, roughly ten minutes into the attack and the second hit at 2115. Since the British agree on the timing of the attack, and Coode observed no damage as he withdrew, my conclusion is that the first attackers (the second, third, and fourth sub-flights) could not have scored a hit.

Since Owensmith and Keane saw a hit, but Coode did not, the first hit must have been scored by somebody that came after Coode and before Owensmith. By process of elimination, this can only mean Keane or Moffatt. Since Keane at no time credited himself with the hit, I conclude that Moffatt got it, though that is really just an assumption. Likewise, since Beale was one of the last attackers, in my opinion, there can be little doubt that his hit was the second one indicated by Lütjens and that it struck Bismarck amidships.

Appendix One - The Men that Torpedoed the Bismarck. (Rank is that held on 24-26 May 1941).

HMS Victorious:

| 825 Squadron: | 5A | Lt.Cdr.(A) Eugene Kingsmill Esmonde, RN (P) Lt. Colin Croft Ennever, RN (O) PO(A) Stanley Edgar Parker, RN Fx.76360 (TAG) |

| 5B | Lt. Neal Gordon MacLean, RNVR (P) T/S-Lt.(A) Leslie Bailey, RNVR (O) NA Donald Arthur Bunce, RN Sfx.631 (TAG) |

|

| 5C | Lt.(A) John Chute Thompson, RN (P) A/S-Lt. Robert Laurens Parkinson, RN (O) PO(A) Ambrose Lawrence Johnson, RN D/Jx.146558 (TAG) |

|

| 5F | Lt. Philip David Gick, RN (P) [DSC 16.9.41] S-Lt.(A) Valentine Kay Norfolk, RN (O) PO(A) Leslie Daniel Sayer, RN Fx.76577 (TAG) |

|

| 5G | Lt.(A) William Francis Cuthbert Garthwaite, RNVR (P) S-Lt.(A) William Anthony Gillingham, RNVR (O) LA Henry Thomas Albert Wheeler, RN Fx.189404 (TAG) |

|

| 5H:V4337 | S-Lt.(A) Patrick Bernard Jackson, RN (P) A/S-Lt. David Anthony Berrill, RN (O) LA F. G. Sparkes (TAG) |

|

| 5K | Lt.(A) Henry Charles Michell Pollard, RN (P) S-Lt.(A) David Musk Beattie, RNVR (O) LA Percy William Clitheroe, DSM, RN P/Jx.135706 (TAG) |

|

| 5L | S-Lt.(A) Robert Graham Lawson, RNVR (P) A/S-Lt. Frank Leonard Robinson, RNVR (O) LA Iowerth Llewelyn Owen (TAG) |

|

| 5M | S-Lt.(A) Alexander James Houston, RNVR (P) S-Lt.(A) John Robert Geater, RNVR (O) PO(A) William Johnson Clinton, RN (TAG) |

HMS Ark Royal:

| 810 Squadron: | 2A:P4131 | S-Lt.(A) Kenneth Stuart Pattisson, RN (P) S-Lt.(A) Peter Bishop Meadway, RNVR (O) NA D. L. Mulley (TAG) |

| 2B | Lt. David Frederick Godfrey-Faussett, RN (P) PO(A) V. R. Graham, RN F.55072 (TAG) S-Lt.(A) Lionel Arthur Royall, RN (O) |

|

| 2P | S-Lt.(A) Anthony William Duncan Beale, RN (P) A/S-Lt.(A) Charles Friend, RN (O) LA Kenneth Pimlott SFx.392 (TAG) |

|

| 2M | S-Lt.(A) Clive Morton Jewell, RN (P) LA G. H. Parkinson (TAG) |

|

| 818 Squadron: | 5A:P4219 | Lt.Cdr. Trevenen Penrose Coode, RN (P) Lt. Edmund Squarey Carver, RN (O) PO W. H. Dillnutt (TAG) |

| 5B | S-Lt.(A) Eric Dixon Child, RNVR (P) S-Lt.(A) George Richard Christopher Penrose, RN (O) Reginald Howard Watson Blake, RN (TAG) |

|

| 5C:L9726 | S-Lt. John William Charlton Moffatt, RNVR (P) T/S-Lt.(A) John Dawson Miller, RNVR (O) LA Albert J. Hayman, RN Jx.151230 (TAG) |

|

| 5K | Lt.(A) Stanley Keane DSC, [MiD], RN (P) S-Lt.(A) Rene Irving Whitley Goddard, RN (O) PO(A) Douglas C. Milliner, RN Fx.77749 (TAG) |

|

| 820 Squadron: | 4A | Lt. Hugh de Graaff Hunter, MiD, RN (P) Lt.Cdr. James Andrew Stewart-Moore, RN (OC-O) PO(A) Robert Henry McColl, DSM, RN Fx.76319 (TAG) |

| 4B | A/S-Lt.(A) Michael John Lithgow, RN (P) T/S-Lt.(A) Norman Charles Manley Cooper, RNVR (O) LA J. Russell (TAG) |

|

| 4C:V4298 | S-Lt.(A) Francis Alan Swanton, RN (P) T/S-Lt.(A) Gerald Ashton Woods, RNVR (O) LA J. R. Seafer (TAG) |

|

| 4K:L7643 | Lt.(A) Albert Sidney Smith Owensmith, RN (P) A/S-Lt.(A) Geoffrey George Topham, RNVR (O) PO(A) James Watson Fx.76318 (TAG) |

|

| 4L P4204 | S-Lt.(A) James Robert Nigel Gardner, RN (P) T/S-Lt.(A) John Bristow Longmuir, RNVR (O) |

|

| 4F | S-Lt.(A) Murry Francis Sanders Peake Willcocks, RN (P) S-Lt. Henry George Mays, RN (O) LA R. Finney, RN Jx.156354 (TAG) |

|

| 4G | S-Lt.(A) Anthony Neville Dixon, RN (P) S-Lt.(A) James Francis Turner, RNVR (O) LA A. T. A. Shields (TAG) |

Sources.

Besides numerous non-published Admiralty records, the following published sources were used in writing this article.

Archbold, Rick (Ballard, Dr. Robert G.). The Discovery of the Bismarck. Toronto, Canada: Madison Press Books, 1990.

Brown, David. Carrier Operations in World War II, Volume I; The Royal Navy. Ian Allan, 1974

Grenfell, Captain Russell. The Bismarck Episode. New York: Macmillan and Company, 1964.

Jameson, Rear Admiral-William. Ark Royal 1939-1941. London: Rupert-Hart Davis, 1957.

Kennedy, Ludovic. Pursuit: the Chase and Sinking of the Battleship Bismarck. New York: Viknig Press, 1974.

Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, 1937-38, Volume II: Steamers & Motorships of 300 Tons Gross and Over. London, 1937

Müllenheim-Rechberg, Baron Burkard von. Battleship Bismarck, A Survivor’s Story. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1980

Poolman, Kenneth. Ark Royal. William Kimber & Co., 1956.

Porten, Edward P. von der. German Navy in World War II. New York: Thomas Crowell Company, 1969

Rohwer, Dr. Jürgen and G. Hummelchen. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939-1945, Vol. I & II. New York: Arco, 1973-1974.

Schofield, Vice-Admiral B. B. Loss of the Battleship Bismarck. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1972.

Sturtivant, ISO, Ray. The Swordfish Story. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1993.

_ with Theo Ballance. The Squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm. London: Air Britain, 1994.

_ with Mick Burrow. Fleet Air Arm Aircraft, 1939-1945. London: Air Britain, 1995.

| Home Guestbook Quiz Glossary Help us Weights & Measures Video Credits Links Contact |