|

Home Intro Technical History Crew Models Gallery Kriegsmarine Archives

More Forum  UPDATES UPDATES |

Conference of the Commander in Chief, Navy, with the Führer on 14 November 1940, at 1300.

| Present: |

Oberst Schmundt Fregattenkapitän von Puttkamer |

1. Enemy Situation: For a survey of Britain's situation, see Annex 1.

2. Own Situation. Naval Warfare in Home Waters: Our operations in the Channel have recently been greatly hampered by the weather. Escort of shipping to the Channel, to Norway, and along the Norwegian coast has been carried out without appreciable losses. There has been more extensive activity by British destroyers against the Norwegian coast, and also by British submarines which have lately again been appearing in the Skagerrak. In the night of 6 November operations were conducted by the 1st and 2nd Torpedo Boat Flotillas against the convoy route on the British coast at Firth of Moray. The loss of T6 due to a mine shows that the enemy has protected the coastal route effectively by flanking mine fields.

There is nothing to report on the Atlantic coast. For the sake of our operations and submarine warfare, and in order to bring in prizes and to enable blockade-runners to operate, it is necessary to extend the defenses of our coastal waters.

3. Recent Mine Warfare and Further Plans.

I. Naval Forces:

-

a. Home area: The Channel area off the British coast has been mined.

In the western sector mines were laid by destroyers, in the middle sector by torpedo boats, and on the southeast coast by S-boats.

Plan: The operations are to be continued with the object of effective mining of British coastal waters.

Requirements of operation "Seelöwe" are being taken into consideration.

North Sea: It is planned to extend to the north the German declared area by laying mines to protect the Skagerrak and the sea routes to Norway. The southwestern flanking minefields are to be extended in order to protect the coastal route to the west.

b Foreign waters: Mines are to be laid by auxiliary cruisers in South African, Indian, and Australian waters.

4. Atlantic Submarine Warfare. The great successes of our submarines at the end of October are now decreasing. This is unavoidable, in view of necessary overhauling and relief. It will be offset somewhat by operations of Italian submarines in the North Atlantic. The Italian successes cannot yet be compared with the achievement of our submarines due to the lack of training and experience of the Italians. But the morale of the crews is good.

Recently there have been appreciable losses in supplies for Britain resulting from the successful warfare waged against merchant shipping by submarines and by the Luftwaffe. Reports from Britain confirm the seriousness of the situation and the anxiety felt there regarding the supply situation. In his last speech Churchill said that the submarine danger is more serious than the continual air attacks, and that large-scale preparations will be necessary in order to meet the very serious dangers from submarines in the coming year. It is therefore imperative to concentrate all the forces of the Navy and the Luftwaffe for the purpose of interrupting all supply shipments to Britain. This must be our chief operational objective in the war against Britain.

In the course of the last operation, U31 (commanded by Prellberg) and U32 (commanded by Jenisch) were lost. Losses up to now have averaged 2.1 per month.

The weakness of British defense and escort forces so far was a great advantage for our submarines. In view of the support given to Britain by the U.S.A. and as the result of new ships built, we must expect a considerable increase in the number of destroyers and anti-submarine vessels. An increase in anti-submarine activity is already perceptible. Therefore the following measures are urgently required:

a. Priority must be given to the submarine program, which is still handicapped by the fact that too many projects have been awarded special priority. Already the state of affairs is such that at the end of 1940, 37 submarines fewer will have been completed than were planned. Negotiations with the Chief of the OKW have been opened to urge that immediate steps be taken to remedy this situation. If these conversations are not successful the Commander in Chief, Navy, will appeal to the Führer!

b. Constant attacks of our Air Force should be aimed at the destruction of British destroyers, escort vessels, and submarine chasers. Every destroyer and defense vessel sunk is of decisive importance for submarine warfare.

The air attacks on Britain up to now have not created the conditions necessary for carrying out operation "Seelöwe". Naval vessels are still stationed in harbors like Portsmouth and Plymouth. The situation must change before any new attempt to carry out operation "Seelöwe" is made. In addition, the Clyde shipyards and other shipyards where new battleships are being constructed must now be bombed, too, in order to bring about a more favorable situation at sea in the coming year.

The Führer confirms the fact that attacks by the Luftwaffe have not achieved the anticipated results either on land or in the case of convoys. On land quite often only dummy installations, etc., were destroyed, while at sea it was found difficult to score hits.

5. Cruiser Warfare:

a. The cruiser SCHEER and the supply ship NORDMARK succeeded during the second half of October in breaking through the North Sea and Iceland area unobserved by the enemy. On 5 November the SCHEER made a surprise attack on a convoy on the Canada route; 85,000 tons were sunk! This was an excellent achievement. Far-reaching strategic effects are to be expected. An immediate reaction on the part of the enemy is evident; the Scapa Group has put out to sea and the Gibraltar Group is in a state of readiness. The enemy will be forced to provide greater protection of convoy traffic. The SCHEER is now proceeding south. The withdrawal of British forces from home waters may later result in conditions favorable for renewed attacks by other units of the fleet on the North Atlantic route.

b. Auxiliary cruisers: Ship "21" [Widder] has returned. Ship "41" [Kormoran] will put out to sea in December, for operations in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. Continued successful operations by all our auxiliary cruisers can be reported. The disposition at present is as follows: One auxiliary cruiser is in the South Atlantic, one in the western part of the Indian Ocean, one in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean; two are operating together in the Pacific on the Australian-Panama route.

Supplies from non-German sources have up to now been secured with only slight losses, in spite of a very sharp watch maintained by the enemy.

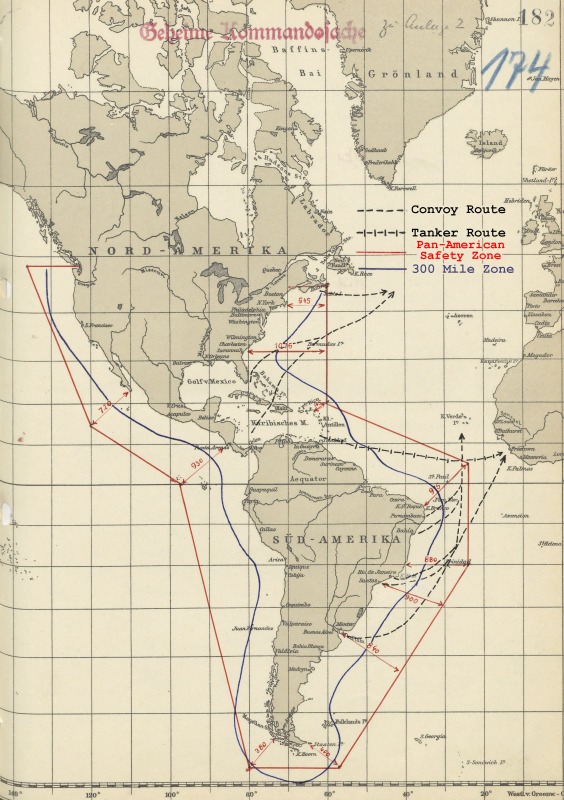

6. The Pan-American safety zone is detrimental to cruiser warfare. It is proposed to change the regulations governing conduct in this zone as soon as the attitude of the U.S.A. becomes more unfriendly, particularly since the British have violated the regulations on numerous occasions. (See Annex 2, with map.)

7. Resumption of Merchant Shipping; Blockade-Runners. So far three prizes, the catapult ship OSTMARK, and the tanker GEDANIA successfully reached the Atlantic coast. Likewise the transfer of some ships from Spain was accomplished. The GEDANIA carried a valuable cargo of whale oil which is of special importance for German margarine supplies.

Preparations for the return or merchant ships from abroad and for merchant traffic with blockade-runners are being planned in cooperation with the Ministry of Economics and the Ministry of Transportation. Supplying the ships, getting them in condition to leave, and contraband control and surveillance by the enemy cause difficulties. A ship is en route to France from Colombia; the escape was well executed. Three ships are ready to sail from Mexico. Four ships are being made ready on the west coast of South and Central America. The return of the motor ships from East Asia is being considered. Four ships are to leave France for South America.

The SCHEER operation is expected to increase the chances for the blockade-runners. Preparations for merchant traffic in the Mediterranean with Italy and Spain are in progress.

8. For a review of the situation in the Mediterranean see Annex 3.

9. Further Plans of the Führer:

-

a. The views of the Seekriegsleitung regarding occupation of islands in the Atlantic.

b. For an evaluation of occupation of the Cape Verde and Canary Islands, see Annex 4.

c. For an evaluation of the strategic importance of Portugal for Britain and Germany, see Annexes 5 and 6.

(1) Canary Islands: They are of importance to the British in case Gibraltar is taken, and they are useful to us as a base for submarines, Panzerschiffe, auxiliary cruisers, and merchant shipping. For this purpose, however, these islands would have to be fully equipped as a base. We must check at once whether sufficient ammunition for coastal fortifications, anti-aircraft guns and ammunition, oil stocks and oil storage space, etc., are available. Spanish troops must be supplemented, in the same manner as the Condor Legion was used [during the Civil War]. All this must be done prior to Spain's entry into the war. Occupation by the British must under all circumstances be prevented in order that they shall have no hold on Spain.

(2) Portuguese Possessions: (For details see Annexes 4 and 5.) The neutrality of Portugal is most favorable to us (see Annex 5). Portugal will maintain neutrality, since she knows that we could drive the British out of Portugal from Spain. Any breach of Portugal's neutrality by us would have a very unfavorable effect on public opinion in the U.S.A., Brazil, and in South America generally, but above all it would result in the immediate occupation of the Azores, perhaps also of the Cape Verde Islands and of Angola, by Britain or the U.S.A.

The Führer believes that the British would occupy the Azores immediately upon our entry into Spain (the Commander in Chief, Navy, has great doubts about this), and that she would later cede the Azores to the U.S.A. The Führer believes that the Azores would afford him the only facility for attacking America, if she should enter the war, with a modern plane of the Messerschmitt type [Me 264], which has a range of 12,600 km. Thereby America would be forced to build up her own anti-aircraft defense, which is still completely lacking, instead of assisting Britain.

The Commander in Chief, Navy, states that the occupation of the Azores would certainly be a very risky operation, but one which, with luck, could succeed. On the other hand it is very doubtful whether we could bring up adequate protection and supplies, and the possibility of holding the islands is quite unlikely in view of a strong British offensive which would certainly be carried out, perhaps with American help. In addition, German naval forces would for a long time be engaged in defensive tasks of escorting supplies instead of serving the main war aim of offensive Operations. Submarines would also have to be used for defense. In this way submarine warfare would be adversely affected, which must not occur under any circumstances. As it is very doubtful whether there are any harbor facilities at all in the Azores for speedy unloading of heavy equipment, or shelters for aircraft and supplies, immediate investigations must be made by both a naval and an air officer. The Führer orders this to be done.

The Commander in Chief, Navy, points out that apart from this Portugal should be influenced at this point to fortify the Azores strongly and to defend them. The Commander in Chief, Navy, considers occupation of the Cape Verde Islands and of Madeira unnecessary, since they would offer a useful base neither to us nor to the British.

10. Regarding Russia. The Führer is still inclined towards a showdown with Russia. The Commander in Chief, Navy, recommends postponing this until after victory over Britain, since demands on German forces would be too great, and an end to hostilities could not be foreseen. During the war the area so urgently needed for submarine training in the eastern Baltic would be lost, and submarine warfare thereby very adversely affected. Russia will not attempt the showdown on her part in the next few years, since she is at present building up her Navy with the assistance of Germany. She attaches great importance to the 38 cm. turrets for battleships; therefore she will remain dependent on German support in the years to come.

11. The Commander in Chief, Navy, requests permission to buy some Danish torpedo boats to be used as recovery boats at submarine firing exercises; they are urgently needed. The Führer agrees.

12. The Commander in Chief, Navy, reports that construction of submarine shelters in Lorient is proceeding with the help of the Todt Organization. In Heligoland they will be completed shortly. In Kiel, Wilhelmshaven, and Hamburg construction had to be suspended in favor of other work (harbor entrance 4) owing to lack of workers. In Wilhelmshaven they are no longer so urgent because of the removal of the shipyard to Lorient; In Kiel there is good anti-aircraft protection. In Hamburg construction is to be resumed.

13. Construction Work for Operation "Seelöwe": The High Command, Navy, has developed a transport barge carrying three tanks at a speed of 13 to 15 knots. A few samples of this model are being built. The engineers are constructing, with special priority, craft capable of carrying one tank. They have a speed of 5 knots and are less seaworthy. Colonel von Schell is constructing, with special priority, a hydrofoil motorboat in competition with the Navy. The Commander in Chief, Navy, requests a new order to the effect that vessels for operation "Seelöwe" are to be constructed only by the Navy. The Führer gives instructions to this effect to the OKW.

14. The Commander in Chief, Navy, reports on difficulties in the political administration of Norway and requests that Quisling and Hagelin be received by Minister Lammers to report. The Fúhrer agrees.

The Commander in Chief, Navy, mentions that the question of Brittany is still being pursued in certain quarters; this is not important in the first place, and besides, in view of the present relations with France, it should not be touched on. The Führer gives instructions that the Brittany question is to be dropped. (Reichsleiter Bormann).

15. The Commander in Chief, Navy, raises the question of money awards which are paid by the Luftwaffe for sinking naval vessels. He considers a general ruling necessary for the Wehrmacht but rejects its application as far as the Navy is concerned.

Annex 1

Critical Examination of Britain's Situation on 21 October 1940.Extract from the War Diary of the Seekriegsleitung.

Information received regarding British preparations for operations and convoy movements indicates to the Seekriegsleitung that the enemy has clearly recognized the dangers which threaten him in the Mediterranean and African areas. He presumably considers these decisive for the outcome of the war and is determined to counter them with the utmost energy and the greatest speed. Very definite and convincing indications of this intention are the following: The utterances of British statesmen and military leaders regarding Britain's imminent offensive activity; important changes in personnel, such as the appointment of Tovey as Commander in Chief of the Home Fleet and Portal as Commander in Chief of the RAF; lively political and diplomatic activities in Washington, Egypt, Turkey, and Palestine; considerable military preparations in Egypt, West Africa, and the British Isles. These indications are supplemented by the indisputable fact that the British people have up to now shown extraordinary morale and most remarkable stamina in the face of very heavy blows dealt by our Air Force and of very hard trials caused by the loss of life, property, and personal freedom. With this support the British leaders are still undaunted in their resolve to carry on the war with all the means in their power.

The British leaders and the British people have been shaken out of their lethargy and their laissez-faire, mercenary attitude by the gravity of their situation. The fact is more and more recognized that the British Empire, which hitherto appeared to be unconquerable, is in very great danger. In the opinion of the Seekriegsleitung, they now fully realize that it is certainly late, but, as they think, not at all too late, and they are resolved to take up the fight, which they have avoided so far. In all sectors with increased energy. They are determined to break away from their hitherto very strong defensive attitude and to try to gain the initiative by offensive action. This inner change in British war policy appears to be unmistakable if political and military developments are observed closely. It was favored and promoted by the following events:

1. The almost exclusive concentration of German war measures on operation "Seelöwe", which barred any large-scale operations by German surface forces.

2. The realization that an invasion has not taken place and, in view of the strength of British coastal and air defense, is not to be expected at least for the present.

3. The generally very weak striking power of the Italian armed forces, combined with tactical weakness, which has led to a very low estimation of Italian warfare and operational capacity on the part of the British, and which has given them time for a hitherto undisturbed intensification of British-defenses on the Suez Canal.

4. Help from the U.S.A., which is already very considerable, combined with the expectation of further strong support after the presidential election.

5. Anxiety regarding further developments in German-French relations, particularly with regard to the situation in West Africa and Morocco, which is of decisive importance for the British position in Freetown and for the whole Atlantic convoy system.

6. Anxiety regarding the possibility of losing their position in Egypt and therefore in the whole Mediterranean.

From the over-all military and political situation there arises the strategic necessity for Britain to take action, in view of the increasingly difficult conditions within the British economy. In the opinion of the Seekriegsleitung, the British leaders are determined to take the offensive, believing that their prospects of success are not unfavorable.

On the basis of this critical analysis of the British attitude the Seekriegsleitung is convinced that, considering Britain's urgent need for an improvement in the situation, great operational activity on the part of the British must be anticipated in a very short time. The direction in which the main thrust of British operations will be made is not yet clear. It will undoubtedly be in the African and Mediterranean area.

In the Mediterranean at present the main British objective will be the strengthening of their Suez position, which is of decisive importance for the outcome of the war. It is not out of the question that Britain is considering the prospects of launching a large-scale offensive herself against the Italian forces in Egypt and Libya and in Abyssinia, after building up her strength sufficiently in the Alexandria area as well as in the East African area (Kenya). The long delay in the Italian offensive has made this possible.

British occupation of Greece is considered unlikely, but the occupation of Crete, which would be of great importance for naval supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean and for defense against an Italian offensive in Egypt, must be considered a very probable British objective in the Mediterranean.

In the Indian Ocean a British landing on Madagascar is quite within the bounds of possibility, according to information received which, however, is not of an official nature.

In the Central African area, the Gulf of Guinea is at present presumed to be the focal point of operations, with the object of offensive activity against Gabon. A renewed assault on Dakar from the sea is possible but unlikely for the time being after the last fiasco.

No preparations for operations against French Morocco, aimed at Casablanca, or for a strategic expansion toward the North African Mediterranean coast are yet apparent (with the exception of reports received today from the Attaché in Washington). Such operations would fit in with the whole strategic aims of Britain in the Mediterranean and African area, however, and thus cannot be considered out of the question. Whether they are possible depends entirely on the attitude of the French armed forces and the French population in these areas. The prospects for Britain will decrease all the faster the sooner a final settlement is reached for the relations between Germany and France on the basis of a European alliance.

The Seekriegsleitung is convinced that the activity which is generally anticipated will not be restricted to foreign theaters of war, but will also make itself felt very soon in home territory. The Seekriegsleitung expects actions with light surface forces against the Norwegian coast and in the Bay of Biscay; increased operations by submarines in the North Sea, on the south and west coasts of Norway, and in the Skagerrak, the possibilities for which are now once more promising even in difficult areas due to the long, dark nights in autumn and winter; also increased blockade activity in the Iceland-Faroes area and off the Atlantic coast of France and Spain.

Offensive action by naval forces will be supplemented by lively activity on the part of the still unbeaten RAF, which, since an imminent invasion is unlikely, is freed of obligations arising from German landing operations. In addition to operations against naval targets and harbor Installations in the occupied countries, their activities will probably extend to more intense and directed attacks than heretofore against targets in Germany of importance to the war effort.

To sum up, the present picture of the enemy situation gives the impression of imminent activity in British warfare, caused by the pressure of events, and reveals without doubt certain danger points in Axis warfare.

The Seekriegsleitung sees no reason for alarm with regard to the situation, considering the progress of the war and the strategic position which has been achieved by military or diplomatic means. The possibilities afforded the British leaders for their intended offensive should not be over-estimated. They are restricted by the extraordinary difficulties to which the British Empire as a whole is subject and by the weaknesses of the British position with regard to materiel, personnel, and supplies, particularly in foreign waters.

The Seekriegsleitung considers it unlikely, provided a careful watch is kept on future developments, that the British can succeed in effecting a change in the war situation with the operational possibilities available to them. It is, however, of the opinion that it is necessary to recognize fully the possible sources of danger arising from the development of the general situation in the Mediterranean and African area, and to combat them without delay by political and military countermeasures.

Annex 2

Proposal to amend Existing Regulations relating to the Pan-American Safety Zone, since this Zone obstructs Cruiser Warfare.Atlantic ships have instructions to seek no engagements in the Pan-American safety zone (see map). Possibilities for taking effective action against enemy merchant ships are therefore considerably restricted, since enemy shipping and in particular the La Plata trade keeps to a large extent to this area.

The Panama declaration states that the South American Republics wish to maintain strict neutrality during the present war, and that by establishing a safety zone in which engagements are to be prohibited they wish to protect their countries and people from the effects of the present war as far as possible. Since the U.S.A. and other American republics have relinquished strict neutrality and have openly shown this, e.g., by the sale of destroyers to Britain and by innumerable utterances by American statesmen, the safety zone, recognized neither by Great Britain nor by Germany, has been divested of its neutral character. It is very obvious that this safety zone benefits British interests alone. The zone provides protection for enemy ships only, since there is no appreciable German shipping. Enemy naval forces need to be used for the protection of merchant ships only from the points where these are forced to leave the zone. This permits more effective protection of enemy merchant ships against German attacks, or else economy in the use of naval forces.

It is therefore proposed to permit German naval forces to make attacks in the safety zone. The Seekriegsleitung expects no serious political repercussions on the attitude of the American countries toward Germany, as long as attacks are not made too close to the American coast.

The Seekriegsleitung, for its part, suggests a zone of about 200 to 300 miles. Possibly German naval forces which have made attacks in the safety zone would, however, have to reckon with the fact that the American nations will take measures against them, i.e., intern them in case they are forced to put into American harbors. Hitherto, however, no alterations have been announced in the neutrality regulations of the American nations.

At present the Führer does not wish to take up the matter with the U.S.A., but if relations should become more strained he will reconsider the matter.

Appendix 1 to Annex 2

Appendix 2 to Annex 2

Violations of the Pan-American Safety Zone.1. Tanker EMMY FRIEDRICH. Stopped on 24 October 1939 by the British cruiser CARADOC in the vicinity of the Yucatan Straits and scuttled by her own crew.

2. Steamer USSUKUMA. Stopped on 6 December 1939 off Bahia Blanca, Argentina, within the safety zone by a British warship, and scuttled by her own crew.

3. Motor Vessel DUESSELDORF. Stopped on 15 December 1939 off the Chilean coast near Caldera 6 to 7 miles from the coast by the British cruiser DESPATCH. The sea cocks were opened, but the ship not sunk. Brought in by British prize crew.

4. Steamer ARAUCA. Stopped on 19 December 1939 near Ft. Lauderdale within North American territorial waters (i.e., within the three mile zone) by the British cruiser ORION and fired on; finally escorted by three U.S.A. aircraft.

5. Steamer COLUMBUS. Stopped on 19 December 1939, 300 miles northeast of Cape Henry, Virginia, within the safety zone by the British destroyer HYPERION and scuttled by her own crew. The COLUMBUS was escorted by the American cruiser TUSCALOOSA, which directed the British naval vessel to the German ship.

6. Steamer WAKAMA. Stopped on 13 February 1940 off the Brazilian coast (between Cabo and Sao Thome) within the safety zone by a British cruiser and scuttled by her own crew. Life boats were fired on with machine guns.

7. Steamer TROJA. Stopped on 1 March 1940 in the Caribbean Sea near Aruba by a British cruiser, set on fire by her own crew and sunk.

8. Motor Vessel HEIDELBERG. Stopped on 1 March 1940 in the Caribbean Sea on the north coast of Venezuela by a British cruiser and scuttled by her own crew.

9. Motor Vessel HANNOVER. Stopped on 8 March 1940 on the east coast of the Dominican Republic within territorial waters by a British (or French) destroyer and set on fire by her own crew after the sea cocks were opened.

10. Motor Vessel WESER. Taken on 26 September 1940 west of Manzanillo, Mexico, probably within the safety zone by the Canadian auxiliary cruiser PRINCE ROBERT and brought in to Esquimalt, British Columbia.

Annex 3

Evaluation of the Mediterranean Situation.1. The consequences of the independent offensive by Italy against Greece, which is not in accordance with the interests of our combined war activities, are as follows:

-

a. Britain's naval strategic position in the eastern Mediterranean is decidedly improved by the exploitation of naval and air bases on Crete, the Peloponnesos, and Lemnos.

b. Britain has gained in prestige in the Balkan area, Near East, Egypt, and U.S.A., while Italy has lost prestige correspondingly.

c. Conditions for the Italian Libyan offensive against Egypt have deteriorated. The Seekriegsleitung is of the opinion that Italy will never carry out the Egyptian offensive.

The Italian offensive against Greece is decidedly a serious strategic blunder; in view of the anticipated British counteractions it may have an adverse effect on further developments in the Eastern Mediterranean and in the African area, and thus on all future warfare.

The enemy clearly has supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean at present, and it is possible that his position in the Eastern Mediterranean area will become so consolidated that it will no longer be possible to drive the British Fleet from the Mediterranean.

2. The Seekriegsleitung is convinced that the result of the offensive against the Alexandria-Suez area and the development of the situation in the Mediterranean, with their effects on the African and Middle Eastern areas, is of decisive importance for the outcome of the war.

The Seekriegsleitung is of the opinion that the recognition that Britain and the U.S.A. are constantly moving closer together forces us not only to form a European union, but also to fight for the African area as the foremost strategic objective of German warfare as a whole. If we could secure control of the economic block of Europe and Africa in our hands, it would mean that we would possess the decisive bases for raw materials (cotton, copper, and oil) and foodstuffs. For this purpose the first task is to drive the British Fleet from the Mediterranean Sea in order to gain control of the Mediterranean area.

3. a. Importance of Control of the Eastern Mediterranean: This has a decisive effect on Italian powers of endurance in Italy proper, as well as in Abyssinia and the East Africa-Libya area. Very important oil supplies for Spain, Italy, and France would be assured. The necessary supplies of foodstuffs for Spain would be assured, which at present are being sent from Argentina. If Spain enters the war it may be expected that shipments from the West will be greatly reduced. She would therefore be dependent on foodstuffs from the Eastern European (i.e., the Balkan countries and Russia) and the African areas.

The position of the Axis Powers in the Balkans, Asia Minor, Arabia, Egypt, and Sudan would be assured once and for all. Raw materials found in these countries would be included in the German-Italian-Spanish-French economic sphere.

A base for attacks against the British Colonial Empire in East Africa would be acquired, and a threat to India would be created.

b. Importance of Control of the Western Mediterranean including Elimination of Gibraltar: The North African area would be under our control and this supply base for Spain and France would be secured. Any attempt at desertion on the part of the French Colonies in North Africa would be prevented. Uninterrupted supplies from the North African area, which are of vital importance for Spain and France and of considerable importance for Germany, would be guaranteed. A base for attack against British West African colonies would be acquired.

4. Deductions:

a. Occupation of Gibraltar and control of the Western Mediterranean, although very important, are not sufficient in themselves. Domination of the Eastern Mediterranean is also urgently necessary, since this is of decisive importance, both strategically and economically, for further warfare; it is possibly even decisive for the outcome of the war. This is all the more true, if Britain receives little American support. By eliminating British bases and possibilities of operation in the Western and Eastern Mediterranean, the British Fleet would be driven out of the whole Mediterranean area and possibly destroyed.

b. The Italian armed forces have neither the leadership nor the military efficiency to carry the required operations in the Mediterranean area to a successful conclusion with the necessary speed and decision. A successful attack against Egypt by the Italians alone can also scarcely be expected now. The Italian leadership is wretched. They have no understanding of the situation; above all they have not yet perceived in what manner their offensive against Greece primarily damages Italy's powers of endurance. Any opposition offered by the Italian Armistice Commission must be overruled. (Recently it requested disarmament of Oran and Bizerte, while Germany wishes to strengthen France in North Africa.)

c. From the standpoint of the over-all conduct of the war, Germany has a decisive interest in solving the Eastern Mediterranean problem according to German-Italian needs. The Seekriegsleitung is of the opinion that Germany should certainly not be a disinterested spectator in the development of the situation in the Eastern Mediterranean, in view of the close connection between victorious German warfare and the Mediterranean-African problem.

The Seekriegsleitung therefore considers the following necessary:

(1) The German leaders responsible for the conduct of the war must in future plans take into account the fact that no special operational activity, or substantial relief or support, can be expected from the Italian armed forces.

(2) The entire Greek peninsula, including the Peloponnesos, must be cleared of the enemy, and all bases occupied. If the Italians have in mind only a restricted operational purpose in Greece, an appropriate change in policy should be suggested to them immediately. The occupation of southern Greece and western Egypt (Marsa Matruh) would considerably reduce the value of Crete for the enemy.

(3) The enemy should be forced out of the Mediterranean by utilizing every conceivable possibility. In this connection the demand that Italy carry out the Egyptian offensive must be maintained and should be supported by Germany in every possible way.

An offensive through Turkey can scarcely be avoided in spite of all difficulties.

The Führer expects good results from seizing Gibraltar and closing the Mediterranean in the west; subsequently Northwest Africa must be secured. An independent offensive by Germany against Greece although not until 10 to 12 weeks from now, and then with 10 to 12 divisions - should secure Greece for us. The Suez Canal should be mined. After taking Marsa Matruh, a German bomber squadron should be stationed there, in order to attack Alexandria and weaken the British Fleet. The Italian bomber squadron should be withdrawn from the north, where it is being used for attacks against the British Isles, and returned to Italy, with the suggestion that the Italian squadrons have as their main objective weakening of the British Fleet in the Mediterranean.

Annex 4

Brief Examination of the Value of the Cape Verde Islands and the Canary Islands.I. Cape Verde Islands.

1. For the Enemy: They can he used for the following: Substitute for or supplement to Freetown; blockade of Dakar; partial substitute for Gibraltar; patrol of the West African coastal route and the route from Freetown to Natal. There are no serviceable harbors. The islands are little suited for bases. Water is scarce and the climate is bad. There is danger Of air attacks from the relatively close Senegalese Coast.

2. For Germany: If Dakar can be used, the value of the Cape Verde Islands lies only in the fact that the enemy is deprived of their use. If Dakar cannot be used, an attack on the Cape Verdes will not be possible. Possibilities of exploiting the islands for our own naval warfare are few. There would be certain advantages as far as air reconnaissance along the African West Coast is concerned.

3. Execution of the Operation: The islands are 400 miles from Dakar. Operations by our own defense forces are possible only from African bases; the same applies to French forces. These, however, are scarcely sufficient.

There would be difficulty in obtaining transport vessels. Cooperation with the French would be necessary. Our own forces would have to be transported first by land or air to Dakar. The element of surprise could not be relied upon; therefore such an operation is considered scarcely possible. Air support would be difficult owing to great distance; supplies by air even as far as Dakar would require large forces. It would be extremely difficult to set up an effective island defense. There would be no possibility for moving supplies, owing to enemy naval supremacy. It would be necessary to supply everything, however, beginning with drinking water. The distance from Brest is 2,250 miles, from Gibraltar 1,500 miles, from Dakar 400 miles.

4. Political Aspect: The Cape Verde Islands are Portuguese. An occupation contrary to the wishes of Portugal would be inexpedient, since another assault on a small neutral state would intensify enemy propaganda and support U.S. warmongers. In this case the results could be particularly unfavorable, since success of the operation is not assured, and it is not at all certain that the islands can be held.

The British would immediately occupy the Azores and would be in a position to advance against Portuguese possessions in Africa. Portugal's neutrality is of special importance also in view of South America, particularly Brazil.

5. Summary: The islands are of little value for the enemy as well as for us. They are of no help to our war strategy. Occupation could be carried out only with strong French cooperation, and even then it would involve great risks. It would not be possible to maintain the position for any length of time. The political effect would be very detrimental.

II. Canary Islands.

1. For the Enemy: They provide a good island base. There are serviceable harbors and good defense facilities, but there is danger of air attacks from the nearby African coast. After the loss of Gibraltar and Freetown, they would be strategically important as a base for Middle Atlantic and Gibraltar forces, and also as a convoy assembly point.

2. For Germany: The main harbors of the islands could be utilized for naval warfare as bases for submarines, auxiliary cruisers, Panzerschiffe, and for supplies for task forces. This would be possible, however, only if forces for defense against naval and air attacks were sufficient. These defense forces would have to be provided chiefly by Spain and secured by German personnel and materiel (similar to Condor Legion).

3. Execution of Operation: Accurate intelligence on the strength of the island defense would be necessary, also preparation for the necessary reinforcement by the Spaniards with German participation. Reinforcement would be possible only before Spain's entry into the war, since Spanish naval forces are not strong enough to break through an enemy blockade. Use of our own naval forces for this task would be risky and undesirable. It would be feasible to transfer German forces to the Canary Islands from Casablanca before Spain enters the war, but it would be a difficult operation owing to the great distance (550 miles) and the absence of the element of surprise. Possibilities for shipping supplies after Spain's entry into the war would be extremely poor. The distance from Brest is 1,550 miles, from Gibraltar 750 miles, and from Casablanca 550 miles.

4. Political Aspect: Secret German participation in reinforcing the islands would have little political effect. The entry of Spain into the war is expected. French participation is undesirable owing to relations with Spain; at best Casablanca could be used as a port of embarkation and French transport space could be used. In case of French participation, German supervision is absolutely necessary.

5. Summary: The islands are of obvious value to the enemy if Freetown and Gibraltar are lost. They would be useful to a certain extent for our own war activities also. A preliminary requirement is reinforcement of the island defenses before outbreak of war. French cooperation is desirable, but only in transport matters.

Annex 5

Strategic Importance of Portugal for Naval Warfare.I. For the Enemy: Use of Portuguese bases on the European mainland would facilitate the blockade of the area under German control and would simplify the tasks of the British naval forces in the eastern Atlantic. If Gibraltar were lost, the Strait of Gibraltar could be patrolled from Lagos. In view of the enemy's great resources Lagos could be equipped as a base within a short time. From the Portuguese coast it would be easy to watch the northern and southern Spanish harbors; at the same time, it would be more difficult for us to use them for our own operations.

The strategic value of Portuguese harbors for the enemy would be adversely affected by the possibility of German pressure from land and from the air, which the enemy would never be able to resist even together with Portugal. Therefore it may be taken for granted that the strategic importance, which Portugal undoubtedly has for the enemy, will be of short duration. Consequently the occupation of Portugal herself by the enemy is unlikely.

Every action by the enemy, either together with Portugal or against her, which is provoked by our own measures gives the enemy an excuse for moving into Portuguese possessions.

Apart from the consideration of territorial gains, the strategic value of these possessions must be rated high since Germany cannot threaten the occupation. The Azores would be the most useful to the enemy for carrying out his war aims.

II. For Germany: Utilization of Portuguese harbors for our own naval warfare would extend the scope of all our activities in the Atlantic: On the surface, under water, and in the air. This extension, of course, would also be afforded by Spain's participation in the war, but coastal communication between northern and southern Spain would be facilitated by exploiting Portugal too. Disadvantages would be the weak defenses of Portuguese harbors, except the mouth of the Tagus River and Setubal, and the great strain to which our own defense forces are already subjected.

The inclusion of the Portuguese mainland into our sphere would necessarily result in the annexation of Portuguese possessions by the enemy, and would give him an easy pretext to do so. Possession of the Azores above all would be a disadvantage to us since in enemy hands they would limit our own use of the Iberian coast.

III. Deductions: It would appear expedient, if Spain participates in the war, to bring effective pressure to bear on Portugal in order to insure a neutrality which is friendly towards us and is firmly resolved to resist Britain. There should be pressure to reinforce the Azores; propaganda about intended enemy landings there could prepare the ground beforehand.

Portugal must be supported by reinforcing her defenses with German equipment. If necessary, the prospect of gaining possession of British colonies after the conclusion of peace could be held out to Portugal.

The advantage of this action would be friendly neutrality prepared for defense, which would safeguard the use of Spanish harbors for German warfare while excluding the possibility of enemy attacks on Portuguese possessions. Entry by force into another small neutral country, giving incentive to enemy and U.S.A. propaganda, would be avoided. In view of the close cultural and historic ties existing between Portugal and Brazil, the regard shown for Portugal would also have favorable reactions in South America.

Annex 6

The Significance of Portugal for the War Economies of Britain and Germany.I. Significance for Britain: Britain obtains oil of turpentine, turpentine resin, tungsten concentrate, sulphur ore, tin ores, and sardines in oil in small quantities, pit props in larger quantities (of special importance in view of the shortage), and cork in large quantities (80% of the output). Absence of Portuguese deliveries would not make a great difference for Britain. However, since former deliveries of pyrite, iron ore, fruits, and esparto grass from Spain would automatically cease as well, the aggregate loss to the British war economy would be considerable, especially in the case of iron and pit prop supplies. In addition, Portugal provides a market for British coal and a transshipment point for goods from the U.S.A. intended for Britain, which up to now have been brought to Portugal in American ships.

II. Significance for Germany: As a result of the disruption of traffic routes since the beginning of the war, German supplies from Portugal. have been limited to very small quantities of tungsten and tin. However, Portugal could attain significance for the German war economy if unrestricted exchange of the commodities listed below were resumed. She could cover Germany's requirements as follows:

-

6% of the tin ore required

8% per cent of the important alloy metals

18% of the tungsten

1/3 of the oil of turpentine

2/3 of the turpentine resin

more than cover the need for cork and sardines in oil

-

Coal (Portuguese peacetime import was 1,000,000 tons).

Mineral oil products (Portuguese peacetime import was 130,000 tons).

Iron, steel, and semi-finished products (Portuguese peacetime import was 160,000 tons).

| Home Guestbook Quiz Glossary Help us Weights & Measures Video Credits Links Contact |